by Timothy McQuiston, Vermont Business Magazine Weekly unemployment claims continue to hold at typical pre-pandemic summer levels: 315, down 79 for the week and 297 fewer than this time last year. The state unemployment rate is also near its low pre-pandemic levels (3.0 percent August). But the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation programs have now expired. In addition, the federal government will not allow the state to pay regular UI claimants an extra $25 a week.

The Legislature was hopping mad that a bill it passed and the governor signed last spring cannot be implemented to help out those still on unemployment with that $25 supplement. Chittenden County Democratic Senator Kesha Ram Hinsdale has even called for Labor Commissioner Michael Harrington's resignation over the matter. A few other legislators have followed suit or are considering doing so.

They said Harrington was aware of a possible problem with the $25 supplement before the special legislative "veto" session concluded in June. They suggest he either willfully withheld the information or was simply incompetent. If they had known, they said, the Legislature could have possibly rewritten the law to meet federal guidelines or found another funding source (it was intended to come out of the state's UI Trust Fund, which is still flush despite the pandemic with $214.4 million in reserves).

Harrington has said he was attempting to figure out the implications of the possible problem throughout the summer.

At his press conference last Tuesday, Governor Phil Scott defended Harrington, who at that moment was being questioned by legislators.

“From my standpoint this is pretty simple. This was a supplemental benefit that was described as a supplemental benefit by the Legislature.

“We had agreed to try and fund this supplemental benefit with the Trust Fund. So we are under certain restrictions. The Trust Fund is just that. We are entrusted to protect the fund and there are certain criteria, restrictions and so forth, details, that we can't misuse the Trust Fund. The restrictions are in place for good reason, so they aren't used for any other purpose other than unemployment.

“So, again, we, with full knowledge of the Legislature, we reached out to the federal government, the secretary of labor in the Biden administration, and asked them if this was an approved use of the funds. They determined after a long period of time that it is not something that we can utilize out of the Trust Fund, which means that it will have to come from other funding sources if we move forward, which means the General Fund.

“I know that there's a lot of conspiracy theorists out there that this is something dark and mysterious that happened, but it really is about the federal government just saying this is not appropriate. You can't do this. And we have to follow the rules and regulations.

“So it's as simple as that. Now we have to go back to the drawing board a bit with the Legislature to see where they want to get the money from.”

Scott added that there is no reason to ask for Harrington’s resignation.

“If I was to ask a commissioner or a member of my cabinet to resign due to them following the law, I think that would be inappropriate in itself. So, no. I think the bottom line is he was just doing his job and we have an obligation. We're entrusted to protect the Unemployment Trust Fund and we're doing just that. We're just trying to follow the law.”

Scott said that short of bringing back the Legislature back for a special session, which he does not intend to do, there is nothing the state can do about this issue until lawmakers reconvene next January. He said the $25 stipend issue is not significant enough to order the Legislature back.

The Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), which includes the popular PUA, has been credited with helping keep the economy afloat while also lowering the poverty rate (see US Census report below). Even in its last week, the FPUC was putting about $3.6 million extra into the hands of unemployed or underemployed Vermonters.

The Vermont Department of Labor was informed September 1 that it will not be allowed to administer a supplemental unemployment insurance benefit that was passed during the 2021 legislative session.

Act 51 of 2021 authorized a $25 per week supplemental benefit for all unemployment claims beginning October 3, to individuals receiving unemployment benefits in the regular state unemployment insurance program.

However, the Vermont Department of Labor was formally notified on September 1 by the United States Department of Labor (USDOL) that the $25 per week supplemental benefit does not meet the federal unemployment insurance program requirements and therefore the State cannot use Unemployment Trust Fund dollars to cover this benefit, as was intended under the legislation.

In May 2021, while the General Assembly was considering this legislation, the Department submitted a formal inquiry to USDOL for guidance on the creation of a supplemental benefit prior to it becoming law. The goal was to ensure any law passed met the federal government’s requirements; however, USDOL did not respond until after the bill passed both chambers and went into law.

“The legislative intent was to create a supplemental benefit structured like the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) program, which added a flat amount to each weekly benefit payment. While this is exactly how USDOL structured FPUC over the last year, we were informed that a similar state program is not permitted under federal unemployment insurance law,” said Commissioner Harrington in early September. “It’s unfortunate we are learning about it after the law passed, but we must now adapt to ensure we comply with federal law.”

The end of the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program on September 4 should start to show a significant drop off next week as the process plays out and the data catches up. Already as of this current reporting week, the FPUC claims are down by just over 1,200 claims out of a now total of 8,116.

Last week there were a total of 3,868 claims, down 507 from the week before but 20,705 fewer than last year. Including the FPUC categories created specifically in response to the pandemic, there were a total of 11,984 claims last week, which is 1,729 fewer than last week and 25,345 fewer than last year.

Once the federal pandemic programs end and payments cease in about a week, another 9,204 claimants will be removed from the UI rolls. This includes the popular PUA program with 5,851 currently enrolled (see data tables below.). In all, about 3.2 million Americans will lose benefits.

Claimants will collect their final CARES Act benefits the week of September 5-10, when they file their weekly claim – for those in PUA and PEUC, this will be their last weekly claim.

“The federal CARES Act programs played an important role in providing temporary assistance to make sure Vermont workers were supported during a time of great uncertainty throughout the last seventeen months” said Commissioner Michael Harrington in August. “Since March 2020, the Department has issued over 2.3 million unique benefit payments to more than 100,000 Vermonters totaling over $1.7 billion.”

Those individuals on regular UI will continue to collect benefits as they are eligible under regular unemployment, but they will no longer see the FPUC supplement.

Employers are hoping that once workers come off UI they will return to the workplace. The evidence from states that chose to end the federal pandemic assistance early does not indicate that workers will necessarily return to those jobs most needed, as in restaurants.

For instance, Missouri ended their benefits at the end of June, but workers did not flood back to those jobs. The Show Me state gave up an estimated $750 million in projected federal, taxable benefits when it closed down the pandemic program.

Nationally, there is a worker shortage. It is acute in Vermont. Many states, like Vermont, are looking for new Americans, including the recent evacuation of refugees from Afghanistan.

COVID also largely stopped immigration, cross-border workers and college students from alleviating the worker shortage. The Canadian border could fully open September 21. The deadline has been put off twice so far because of the Delta variant.

Vermont has a relatively high number of college students. UVM and Bennington College are reporting their largest freshman classes in their history. Middlebury students left campus when COVID hit in the spring of 2020 and are now back.

Governor Scott has said he hopes that between the high vaccine rates, the return of college students and the end of the federal program that there will be some relief for employers, especially in the service industry.

Scott has acknowledged that all that will not solve the worker shortage in Vermont, which he has repeatedly point out was a big problem before the pandemic. He also is aware that workers in those hard-hit industries might simply not want to go back to those jobs, or will seek a career change.

There is some concern that the COVID-19 Delta variant could further keep workers away concerned for their health as it could also keep businesses at lower capacity, as potential customers once again play it safe.

The state has implemented programs to help people change careers.

A free course program through UVM and CCV were quickly snatched up. Upskill Vermont Scholarship Program was launched July 13 with the goal of enrolling 500 Vermont residents through the Fall 2021 and Spring 2022 semesters. All the slots were filled by the end of the first week the program was open.

The worker relocation program to bring new workers to Vermont also was recently launched.

The Vermont unemployment rate for August was 3.0 percent, unchanged from July. This is near the very low pre-pandemic level, but the labor force, despite gains, has not fully bounced back and is still 4,800 workers less than August 2020.

“As these federal programs end, we know we have more work to do. The Department, and especially our Workforce Development team, are already connecting with claimants and employers to help people get back into the workforce and minimize the impact of this change in benefits”, said Harrington.

The Department has continued to connect with unemployment insurance claimants through direct email and phone outreach to provide information on how the end of federal benefits will impact them, as well as what workforce development support services are available to assist them with re-employment.

Workforce Development team members are located at Job Centers now open for expanded hours across the state and are available for both virtual and in-person career consultations.

Local career specialists can assist jobseekers in finding career and training opportunities, as well as employers looking for talent through job promotion, hiring events, and applicant referrals.

Local and statewide teams continue to hold weekly virtual workshops and events, including sessions on resume writing, re-employment strategies, and virtual job fairs. Learn more at Labor.Vermont.gov/Jobs.

The Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) program provides $300 per week in extra pandemic-related unemployment benefits to unemployed and underemployed workers through state unemployment agencies.

States had to opt-in to the program and could then opt out. Vermont has taken full advantage of the program. Governor Scott, however, previously said he would not extend it beyond September 4 because of the persistent worker shortage, even if Congress were to extend the program, which they have not.

NATIONALLY

The August US Jobs Report is out, and reveals the slowest monthly job gains of the year. According to CNBC, the economy added just 235,000 jobs in August, far below the expected 720,000 positions and a fraction of the nearly 1 million added in July.

The revised August report also suggested a faster growing economy in June and July than previously believed.

The Delta variant is at least partly to blame for the now August downturn, according to economists.

For jobless claims for the week ending September 11, initial claims were up about 20,000 to 332,000, according to the US Labor Department. The previous week saw a pandemic low for weekly claims. This week's report is higher than economists' expectations of 320,000.

Also, a new study shows America’s labor crisis surged in August to a record 10.9 million jobs unfilled, and Vermont has the No. 4 largest labor shortage in the country.

The number of unemployed Americans fell to 8.3 million, which means there are mathematically enough jobs for every unemployed American with 2.6 million jobs left over.

CareerCloud on Monday released the study on the Labor Shortage Impact Across America using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Indeed, ZipRecruiter, and CareerBuilder through September 8.

The rankings were determined by comparing the number of unemployed people with job openings across the three major job boards in every state and DC.

Vermont ranks No. 4 with 1.59 job openings per unemployed person.

CareerCloud's 4 Tips to Help Business Owners Fill Jobs During the Labor Shortage:

- Pay Above the Market Rate: For perhaps the first time, minimum wage workers have leverage due to government aid and are holding out for higher pay. The number of $15 an hour job postings has doubled on Zip Recruiter since 2019 and companies like McDonald’s, Amazon and Chipotle have raised pay this year for hundreds of thousands of workers. Business owners of all sizes will need to increase pay to keep up.

- Lean into Remote Work in the Short and Long Term: Giving employees the chance to work from home now, as the delta variant spreads, is a must. Additionally, a McKinsey survey found that even after the pandemic, 52 percent of workers want a hybrid model working from home and the office. Allowing those who can, to work from home will be an enormous long-term incentive.

- Incentivize Commuting for Jobs That Must be Done In-Person: Now that people learned they can work remotely and earn similar money, they do not want to commute. Harvard Business Review research found a 1% increase in distance to work leads to a 4.4% decrease in commuting flow across the country. Employers could subsidize commuting costs, provide a corporate shuttle, and offer longer but fewer shifts.

- Be Flexible with Parental Leave: It is difficult for both parents to return to work with children in and out of school. With no substantive government guidance in place, businesses must act. Hewlett-Packard launched a "Work That Fits Your Life" program that offers six months of fully paid parental leave for new moms and dads with an option to work part-time for up to 36 months. For smaller businesses, being compassionate and flexible with parental leave will attract candidates.

US Census: Expanded Unemployment Insurance Benefits During Pandemic Lowered Poverty Rates Across All Racial Groups

Understanding why earnings for full-time, year-round workers could go up while earnings overall declined requires a deeper dive into who lost their jobs.

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, shutdowns across the country resulted in rapid job loss. In response to soaring unemployment, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in late March 2020. The CARES Act significantly expanded unemployment insurance by $600 a week, broadened eligibility, and extended benefits for an additional 13 weeks.

How did these moves affect the official poverty rate?

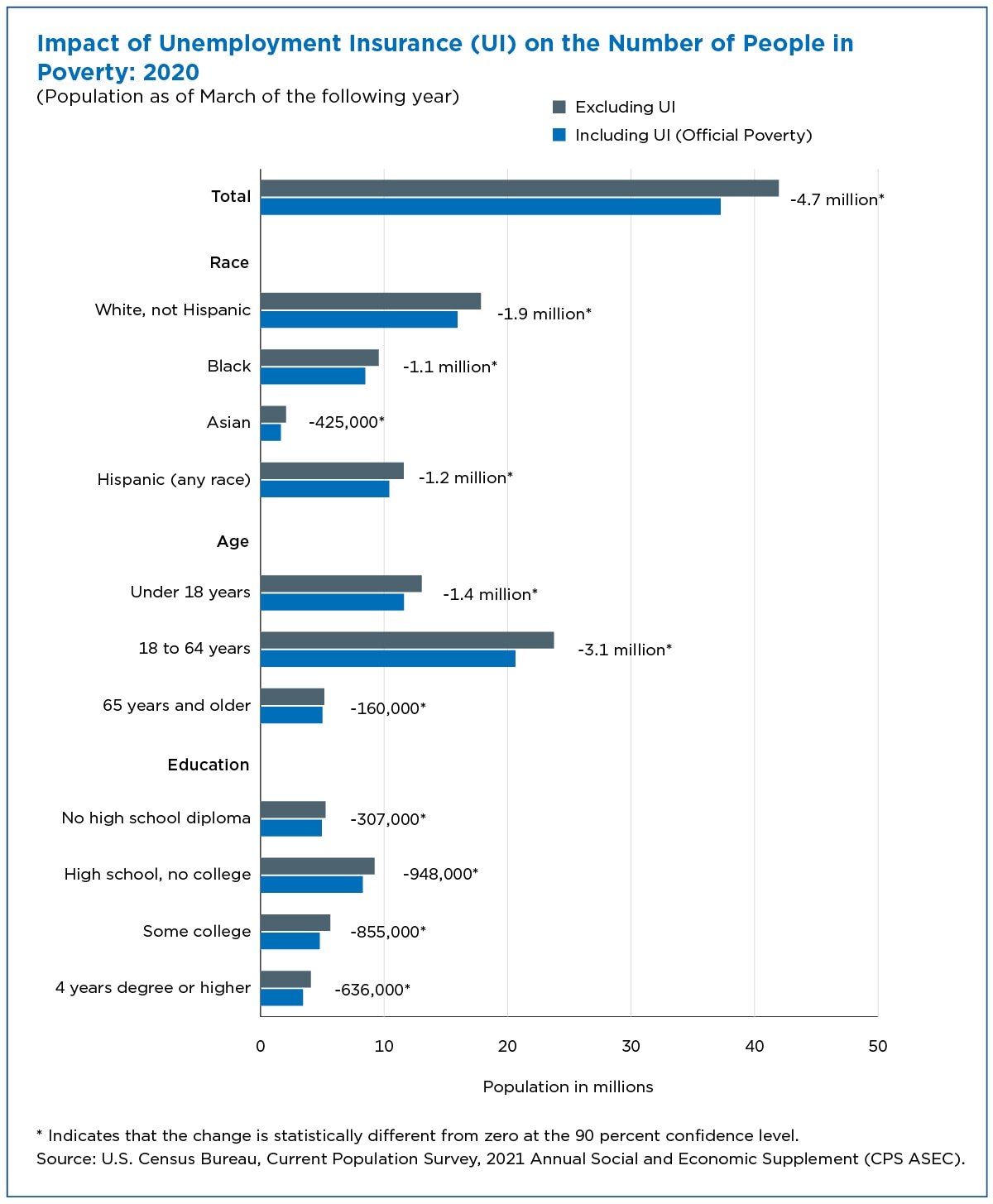

Unemployment insurance (UI) benefits lowered the overall poverty rate by 1.4 percentage points to 11.4% in 2020 and decreased poverty across all racial groups and all age groups, according to U.S. Census Bureau data released recently (differences due to rounding).

Without unemployment insurance, 4.7 million more people would have been in poverty and the overall poverty rate would have been 12.9% in 2020. Less than full-time, year-round workers were among the most impacted by expanded unemployment insurance benefits.

UI lowered the poverty rate for less than full-time, year-round workers by 4.1 percentage points (2.2 million) in 2020.

The effects of UI on poverty rates were particularly stark for some demographic groups.

Race and Hispanic Origin

Unemployment insurance had a large impact on poverty among the Black population, lowering the number of Black people living in poverty by 2.5% (1.1 million).

Impact of UI on other groups:

- For White, non-Hispanic individuals, the number in poverty decreased by 1.0% (1.9 million).

- For Hispanic individuals, the number in poverty dropped by 1.9% (1.2 million).

- For Asian individuals, 2.1% (425,000) were not in poverty due to UI.

The decline in poverty rates between Asian and Hispanic individuals and Asian and Black individuals were not statistically different.

Age

Unemployment insurance lowered the number of individuals in the United States living in poverty for all age groups in 2020.

UI had the greatest impact on children (under age 18) and the least impact on people 65 and older.

The number of children living in poverty fell by 2.0% (1.4 million) after including the value of UI while the number of people ages 18 to 64 living in poverty fell by 1.6% (3.1 million).

Among people ages 65 and older, UI pulled only 0.3% (160,000) out of poverty.

Educational Attainment

Unemployment insurance lowered the number of people living in poverty across all educational attainment groups.

UI had the smallest effect on the poverty rate of those with a bachelor’s degree, keeping only 0.7% (636,000) of these individuals out of poverty.

The effects were higher for all other attainment groups:

- For those with some college, 1.5% (855,000 people) were not in poverty due to UI.

- For those with a high school diploma but who did not attend college, the number in poverty dropped 1.5% (948,000).

- For people without a high school diploma, the decline was 1.5% (307,000).

The percentage point decline in poverty rates between those without a high school diploma was not significantly different from the decline in poverty rates for those with a high school diploma who did not attend college or attended some college.

Neither the decline in poverty rate nor the change in the number of people in poverty were significantly different between those with a high school diploma who did not attend college and those with some college.

US Census: Fewer Low-Wage Full-Time, Year-Round Workers During COVID-19 Causes Increase in Median Earnings Among Those Still Employed

Income statistics released by the U.S. Census Bureau today show a 2.9% decline in median household income between 2019 and 2020 and a 1.2% decline in the median earnings of all workers. But during the same period, real median earnings of full-time, year-round workers increased 6.9%.

Understanding why earnings for full-time, year-round workers could go up while earnings overall declined requires a deeper dive into who lost their jobs.

In short, earnings grew because the decline in full-time, year-round workers was concentrated among workers with lower earnings and workers in low-wage industries and occupations.

Employment Decline by Earnings

Newly released data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) reveal the significant and uneven impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on the labor market.

There were 13.7 million fewer full-time, year-round jobs in 2020 than in 2019, and most employment decline was among workers earning less than $52,000 — the median annual earnings among full-time workers in 2019 (Figure 1).

The decline in workers earning less than the median accounted for about 84% of the total decline in full-time, year-round employment in 2020.

While the pandemic affected earners in the upper half of the earnings distribution as well, the decline for those earning above the 2019 median was more limited.

It was the larger employment decline of these lower wage jobs compared to the employment decline from the higher wage jobs that drove the increase in median earnings for those still employed full-time, year-round in 2020.

Employment Decline by Occupation

We also examined the decline in full-time, year-round employment across job type (Figure 2). We rank 22 major occupation groups by the median hourly wage among full-time, year-round workers in 2019.

The decline in full-time, year-round work was highest in food preparation and serving related occupations — bartenders, waiters and waitresses, and cooks, for example. Occupations in this broad group accounted for 12.5% of the decline in employment and had the lowest hourly wage in 2019 ($13/hour).

Employment Decline by Industry

Finally, we look at the share of employment decline for full-time, year-round workers by 13 major industry groups. Again, we rank the industries by median hourly wage of full-time, year-round workers in 2019.

The leisure and hospitality industry experienced the largest share of employment decline at 24.3%. This industry also had the lowest median wage among all industries in 2019 ($15/hour). It includes establishments in arts, entertainment, and recreation; accommodation; and food services and drinking places.

The large share of the decrease in full-time, year-round employment in food preparation and serving related occupations and in the leisure and hospitality industry, is not surprising given which businesses had to shutter during the pandemic.

But our analysis shows that the decrease in full-time, year-round employment among these low-wage workers was large enough to substantially change the composition of full-time, year-round workers, which explains why median earnings for full-time, year-round workers increased last year while median earnings for all workers fell.

Information on confidentiality protection, methodology, sampling and nonsampling error, and definitions, is available on this technical documentation page.

Sources: VDOL. US Census. 9.17.2021